Show code

library(SingleCellExperiment)

library(here)

library(rmarkdown)

library(janitor)

library(BiocStyle)

library(ggplot2)

library(cowplot)

library(BiocParallel)

library(patchwork)

source(here("code", "helper_functions.R"))

# NOTE: Using >= 4 cores seizes up my laptop. Can use more on RStudio server.

options(

"mc.cores" =

ifelse(Sys.info()[["nodename"]] == "rstudio-1.hpc.wehi.edu.au", 8L, 2L))

register(MulticoreParam(workers = getOption("mc.cores")))

knitr::opts_chunk$set(fig.path = "C057_Cooney.preprocess_files/")

Setting up the data

We start from the demultiplexed SingleCellExperiment object created in ‘Demultiplexing the Cooney (C057) memory CD4+ T-cell data set’.

Incorporating cell-based annotation

Cell-based annotations are included in the colData of the SingleCellExperiment. We store the counts from the hashtag features as an ‘alternative experiment’.

Show code

# Some useful colours

sample_colours <- setNames(

unique(sce$sample_colours),

unique(names(sce$sample_colours)))

treatment_colours <- c(

"Infected" = "#e41a1c",

"Uninfected" = "#377eb8",

"Unknown" = "grey70")

sce$treatment_colours <- treatment_colours[sce$Treatment]

# NOTE: No replicate_colours because we won't ever colour by this.

Summary

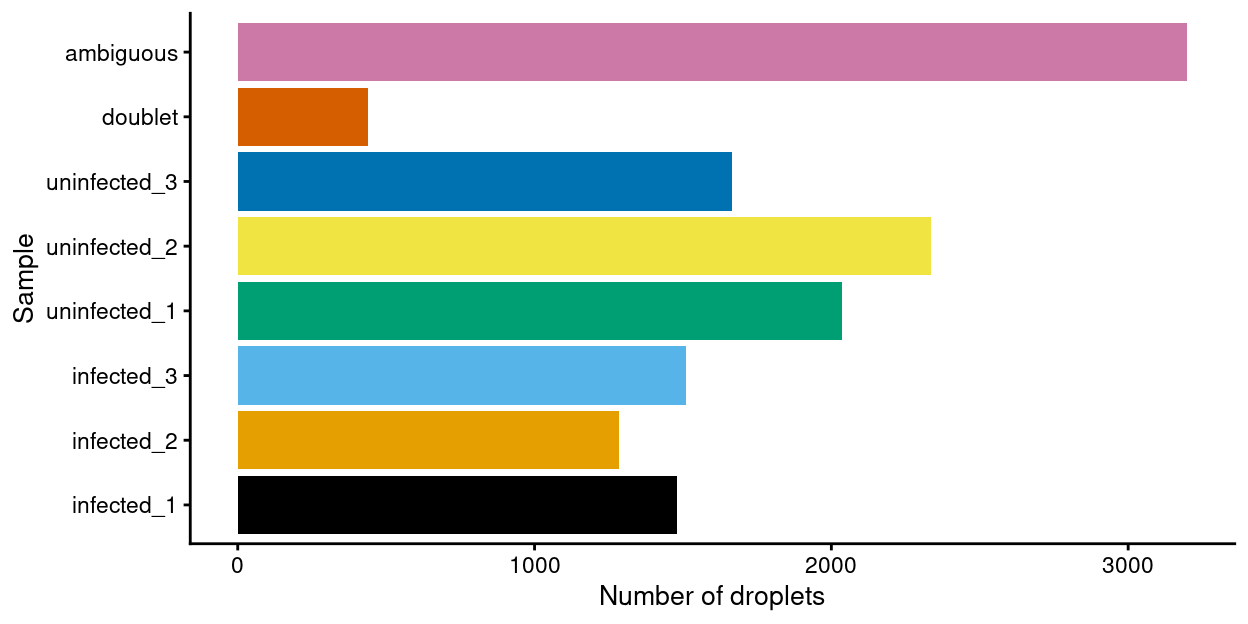

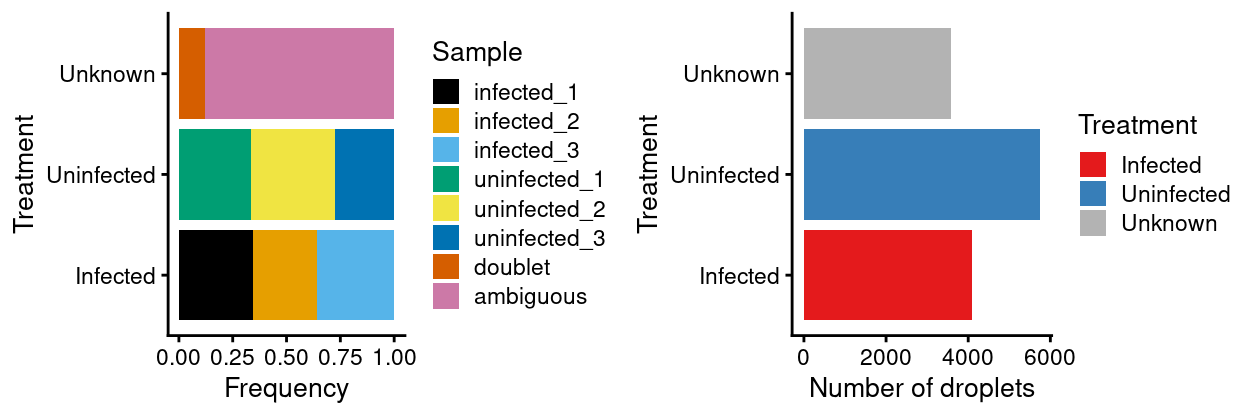

This dataset contains samples from 6 samples, along with ‘doublets’ and ‘ambiguous’ samples. All samples are human memory CD4+ T cells from ‘humanised mice’. Humanised mice are an immunodeficient strain and injected with human stem cells as pups which then differentiate into human hematopoietic cells as the mice mature. Mice were infected or not infected with HTLV, with each condition done in biological triplicate (1 mouse / replicate).

Show code

ggplot(data.frame(Sample = sce$Sample)) +

geom_bar(aes(x = Sample, fill = Sample)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Number of droplets") +

scale_fill_manual(values = sample_colours) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10) +

guides(fill = FALSE)

Figure 1: Breakdown of the samples

Show code

plot_grid(

ggplot(as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Treatment", "Sample")])) +

geom_bar(

aes(x = Treatment, fill = Sample),

position = position_fill(reverse = TRUE)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Frequency") +

scale_fill_manual(values = sample_colours) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10),

ggplot(as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Treatment", "Sample")])) +

geom_bar(aes(x = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Number of droplets") +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10),

align = "h",

ncol = 2)

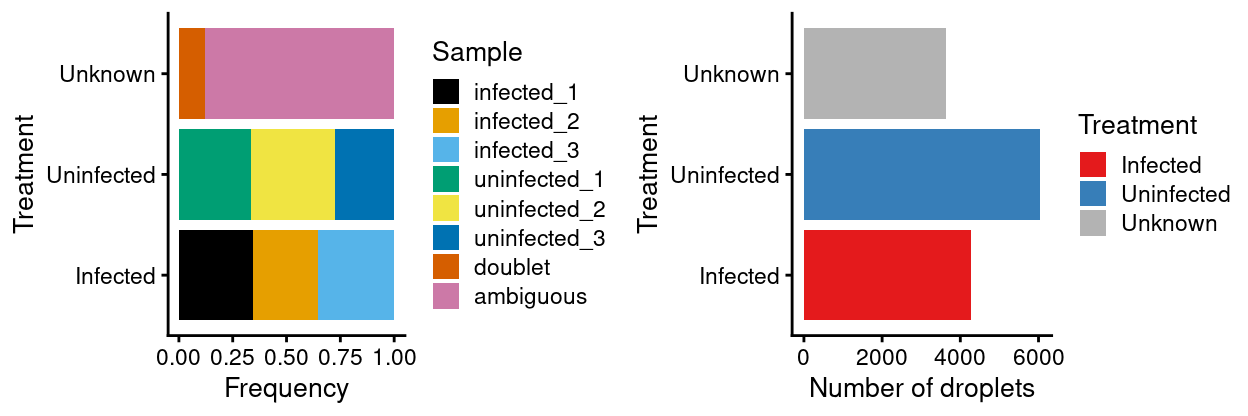

Figure 2: Breakdown of the two treatments.

Incorporating gene-based annotation

Having quantified gene expression against the Ensembl gene annotation, we have Ensembl-style identifiers for the genes. These identifiers are used as they are unambiguous and highly stable. However, they are difficult to interpret compared to the gene symbols which are more commonly used in the literature. Given the Ensembl identifiers, we obtain the corresponding gene symbols using annotation packages available through Bioconductor. Henceforth, we will use gene symbols (where available) to refer to genes in our analysis and otherwise use the Ensembl-style gene identifiers1.

Show code

library(scater)

rownames(sce) <- uniquifyFeatureNames(rowData(sce)$ID, rowData(sce)$Symbol)

# Add chromosome location so we can filter on mitochondrial genes.

library(AnnotationHub)

library(ensembldb)

ah <- AnnotationHub()

EnsDb.Hsapiens.v94 <- query(ah, c("EnsDb", "Homo Sapiens", 94))[[1]]

location <- mapIds(

x = EnsDb.Hsapiens.v94,

# NOTE: Need to remove gene version number prior to lookup.

keys = rowData(sce)$ID,

keytype = "GENEID",

column = "SEQNAME")

rowData(sce)$CHR <- location

Show code

# Additional gene metadata from ENSEMBL and NCBI

# NOTE: These columns were customised for this project.

ensdb_columns <- c(

"GENEBIOTYPE", "GENENAME", "GENESEQSTART", "GENESEQEND", "SEQNAME", "SYMBOL")

names(ensdb_columns) <- paste0("ENSEMBL.", ensdb_columns)

stopifnot(all(ensdb_columns %in% columns(EnsDb.Hsapiens.v94)))

ensdb_df <- DataFrame(

lapply(ensdb_columns, function(column) {

mapIds(

x = EnsDb.Hsapiens.v94,

keys = rowData(sce)$ID,

keytype = "GENEID",

column = column,

multiVals = "CharacterList")

}),

row.names = rowData(sce)$ID)

# NOTE: Can't look up GENEID column with GENEID key, so have to add manually.

ensdb_df$ENSEMBL.GENEID <- rowData(sce)$ID

# NOTE: Homo.sapiens combines org.Hs.eg.db and

# TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene (as well as others) and therefore

# uses entrez gene and RefSeq based data.

library(Homo.sapiens)

# NOTE: These columns were customised for this project.

ncbi_columns <- c(

# From TxDB: None required

# From OrgDB

"ALIAS", "ENTREZID", "GENENAME", "REFSEQ", "SYMBOL")

names(ncbi_columns) <- paste0("NCBI.", ncbi_columns)

stopifnot(all(ncbi_columns %in% columns(Homo.sapiens)))

ncbi_df <- DataFrame(

lapply(ncbi_columns, function(column) {

mapIds(

x = Homo.sapiens,

keys = rowData(sce)$ID,

keytype = "ENSEMBL",

column = column,

multiVals = "CharacterList")

}),

row.names = rowData(sce)$ID)

rowData(sce) <- cbind(rowData(sce), ensdb_df, ncbi_df)

Show code

# Some useful gene sets

mito_set <- rownames(sce)[which(rowData(sce)$CHR == "MT")]

ribo_set <- grep("^RP(S|L)", rownames(sce), value = TRUE)

# NOTE: A more curated approach for identifying ribosomal protein genes

# (https://github.com/Bioconductor/OrchestratingSingleCellAnalysis-base/blob/ae201bf26e3e4fa82d9165d8abf4f4dc4b8e5a68/feature-selection.Rmd#L376-L380)

library(msigdbr)

c2_sets <- msigdbr(species = "Homo sapiens", category = "C2")

ribo_set <- union(

ribo_set,

c2_sets[c2_sets$gs_name == "KEGG_RIBOSOME", ]$human_gene_symbol)

Quality control of cells

Defining the quality control metrics

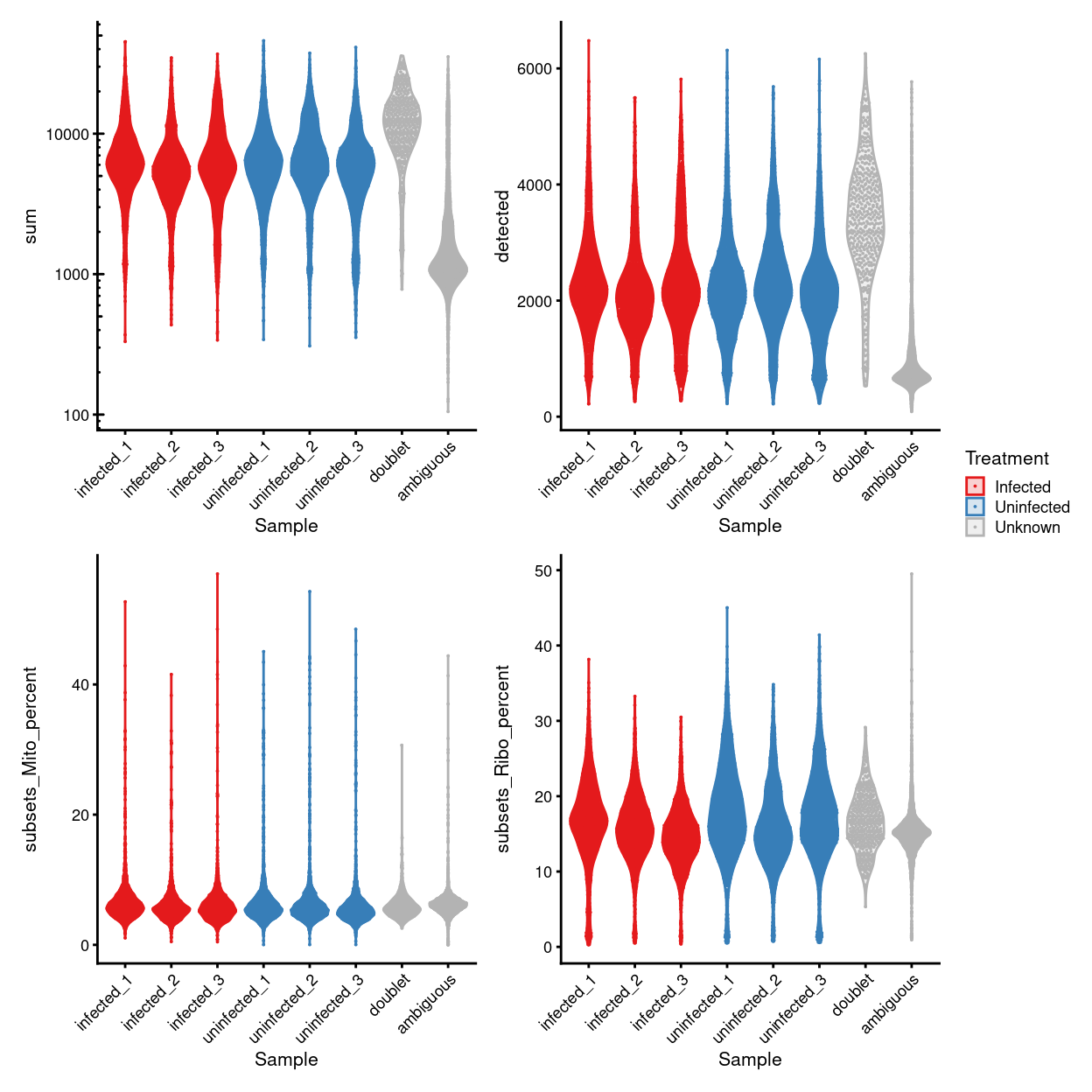

Low-quality cells need to be removed to ensure that technical effects do not distort downstream analysis results. We use several quality control (QC) metrics to measure the quality of the cells:

sum: This measures the library size of the cells, which is the total sum of counts across both genes and spike-in transcripts. We want cells to have high library sizes as this means more RNA has been successfully captured during library preparation.detected: This is the number of expressed features2 in each cell. Cells with few expressed features are likely to be of poor quality, as the diverse transcript population has not been successful captured.subsets_Mito_percent: This measures the proportion of reads which are mapped to mitochondrial RNA. If there is a higher than expected proportion of mitochondrial RNA this is often symptomatic of a cell which is under stress and is therefore of low quality and will not be used for the analysis.subsets_Ribo_percent: This measures the proportion of reads which are mapped to ribosomal protein genes. If there is a higher than expected proportion of ribosomal protein gene expression this is often symptomatic of a cell which is of compromised quality and we may want to exclude it from the analysis.

In summary, we aim to identify cells with low library sizes, few expressed genes, and very high percentages of mitochondrial and ribosomal protein gene expression.

Visualizing the QC metrics

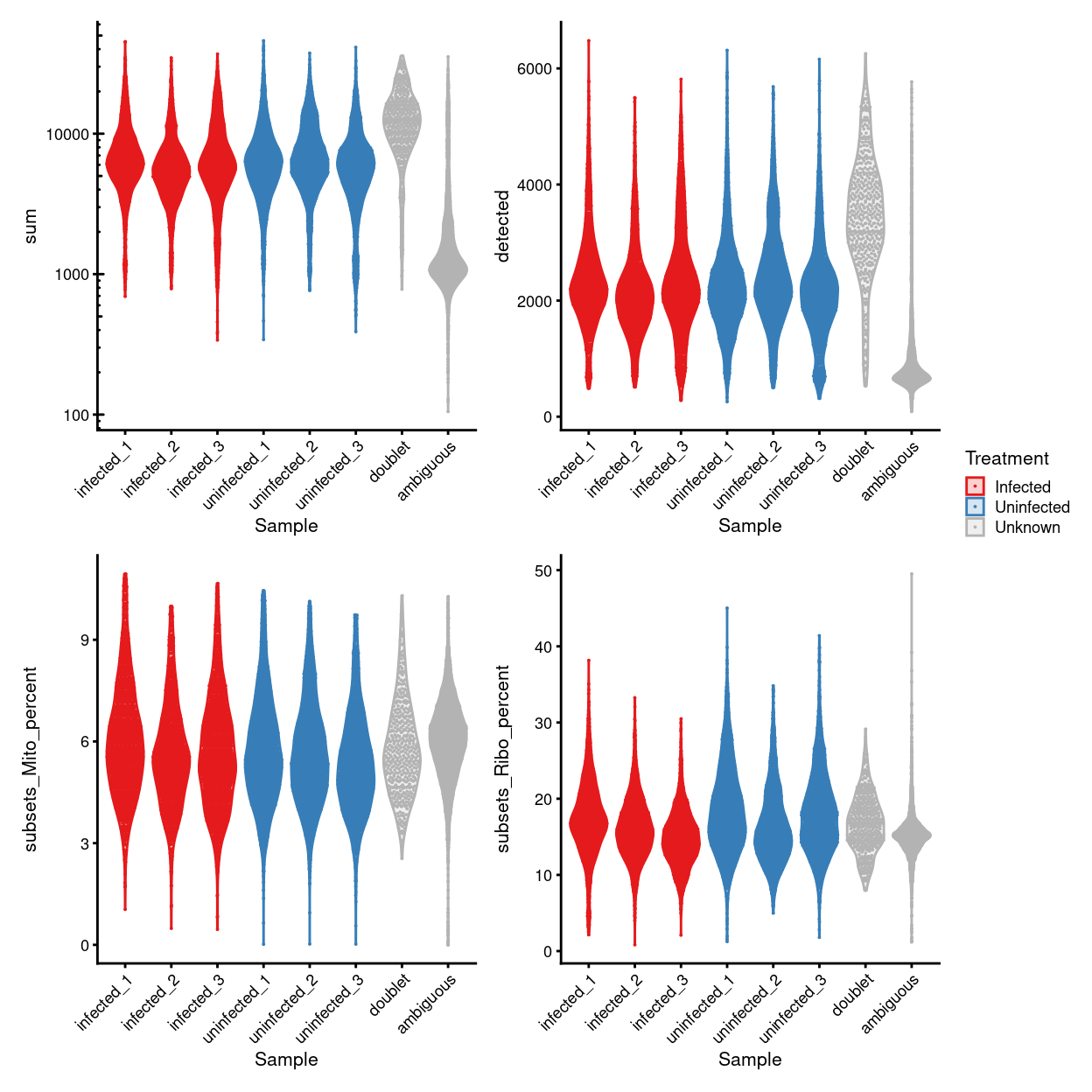

Figure 3 shows that the vast majority of samples are good-quality; the library sizes are in the thousands3, we observe around two thousand expressed genes per cell, and moderate mitochondrial percentages per cell. As we would expect, the doublet droplets have larger library sizes and more genes detected. The ambiguous droplets have notably smaller library sizes and fewer genes detected.

Show code

p1 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "sum")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = sum, colour = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

scale_y_log10() +

annotation_logticks(

sides = "l",

short = unit(0.03, "cm"),

mid = unit(0.06, "cm"),

long = unit(0.09, "cm"))

p2 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "detected")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = detected, colour = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p3 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "subsets_Mito_percent")]),

aes(

x = Sample,

y = subsets_Mito_percent,

colour = Treatment,

fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p4 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "subsets_Ribo_percent")]),

aes(

x = Sample,

y = subsets_Ribo_percent,

colour = Treatment,

fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p1 + p2 + p3 + p4 + plot_layout(guides = "collect")

Figure 3: Distributions of various QC metrics for all cells in the dataset. This includes the library sizes, number of genes detected, and percentage of reads mapped to mitochondrial genes.

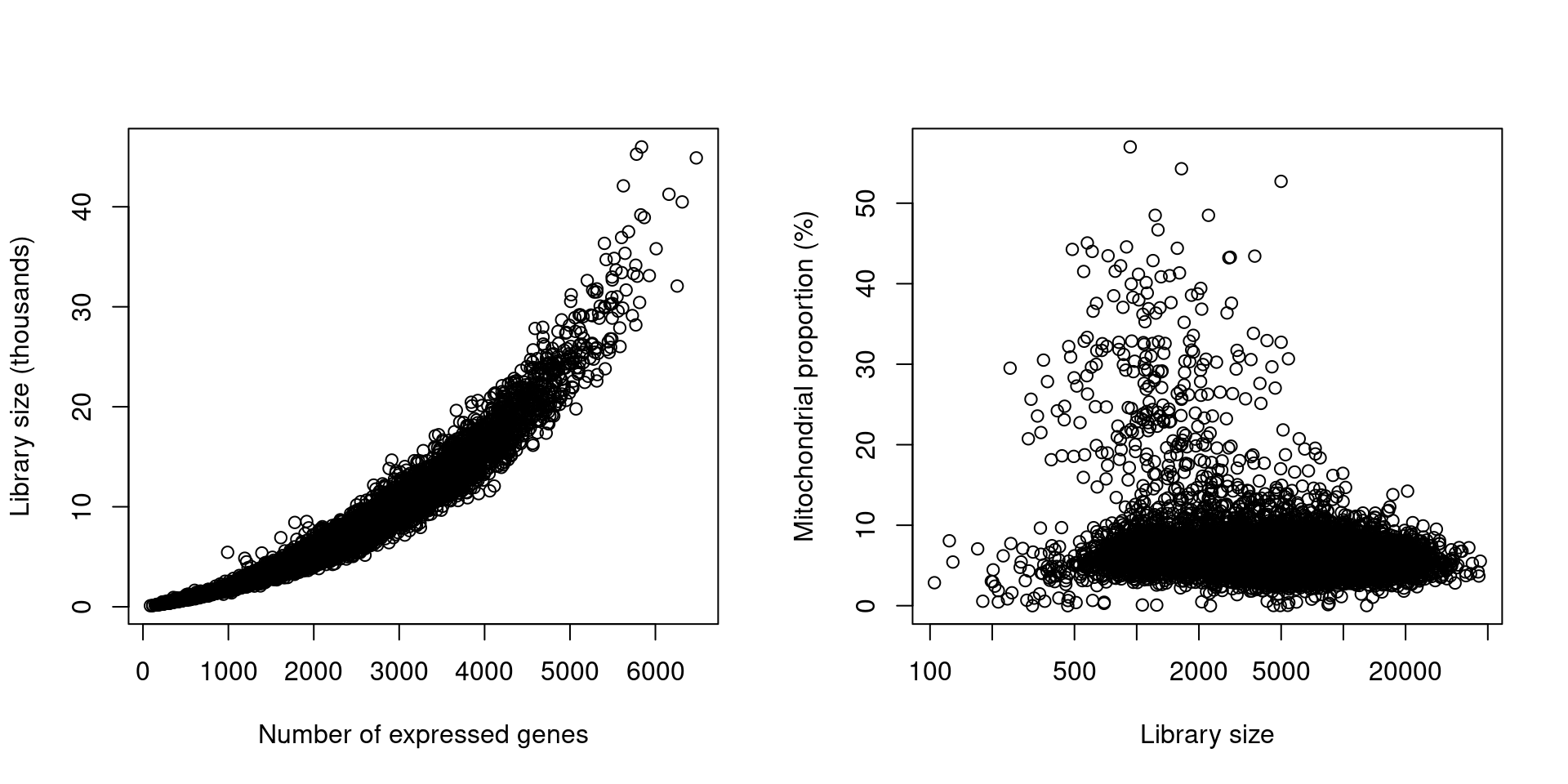

It is also valuable to examine how the other QC metrics behave with respect to each other (Figure 4). Generally, they will be in rough agreement, i.e., cells with low total counts will also have low numbers of expressed features and mitochondrial proportions. Clear discrepancies may correspond to technical differences between batches of cells or genuine biological differences in RNA content.

Show code

Figure 4: Behaviour of each QC metric compared to the total number of expressed features. Each point represents a cell in the data set.

Identifying outliers by each metric

In calling cells from empty droplets, we have already removed cells with very low library sizes or (by association) low numbers of expressed genes. Thus, further filtering on these metrics is not strictly necessary.

Filtering on the mitochondrial proportion provides the most additional benefit in this situation and so we seek to identify droplets with unusually large mitochondrial proportions (i.e. outliers). Outlier thresholds are defined based on the median absolute deviation (MADs) from the median value of the metric across all cells. Here, we opt to use sample-specific thresholds to account for sample-specific differences4.

Show code

sce$batch <- sce$Sample

mito_drop <- isOutlier(

metric = sce$subsets_Mito_percent,

nmads = 3,

type = "higher",

batch = sce$batch,

subset = grepl("^human", sce$HTO))

mito_drop_df <- data.frame(

sample = colnames(attributes(mito_drop)$thresholds),

lower = attributes(mito_drop)$thresholds["higher", ])

The following table summarises the QC cutoffs:

Show code

qc_cutoffs_df <- Reduce(

function(x, y) dplyr::inner_join(x, y, by = "Sample"),

list(mito_drop_df))

colnames(qc_cutoffs_df) <- c("batch", "%mito")

qc_cutoffs_df %>%

dplyr::inner_join(

dplyr::distinct(

as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("batch"), drop = FALSE])),

by = "batch") %>%

dplyr::select(batch, dplyr::everything()) %>%

dplyr::arrange(batch) %>%

knitr::kable(caption = "Sample-specific QC metric cutoffs", digits = 1)

| batch | %mito |

|---|---|

| ambiguous | 10.4 |

| doublet | 10.4 |

| infected_1 | 11.2 |

| infected_2 | 10.0 |

| infected_3 | 10.7 |

| uninfected_1 | 10.5 |

| uninfected_2 | 10.2 |

| uninfected_3 | 9.8 |

The vast majority of cells are retained for all samples.

Show code

sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal <- sce

keep <- !mito_drop

sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal$keep <- keep

sce <- sce[, keep]

data.frame(

ByMito = tapply(

mito_drop,

sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal$batch,

sum,

na.rm = TRUE),

Remaining = as.vector(unname(table(sce$batch))),

PercRemaining = round(

100 * as.vector(unname(table(sce$batch))) /

as.vector(

unname(

table(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal$batch))), 1)) %>%

tibble::rownames_to_column("batch") %>%

dplyr::arrange(dplyr::desc(PercRemaining)) %>%

knitr::kable(

caption = "Number of samples removed by each QC step and the number of samples remaining.")

| batch | ByMito | Remaining | PercRemaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| ambiguous | 48 | 3151 | 98.5 |

| doublet | 13 | 427 | 97.0 |

| infected_3 | 54 | 1455 | 96.4 |

| infected_2 | 57 | 1226 | 95.6 |

| uninfected_2 | 109 | 2226 | 95.3 |

| uninfected_3 | 80 | 1584 | 95.2 |

| uninfected_1 | 101 | 1934 | 95.0 |

| infected_1 | 76 | 1403 | 94.9 |

Checking for removal of biologically relevant subpopulations

The biggest practical concern during QC is whether an entire cell type is inadvertently discarded. There is always some risk of this occurring as the QC metrics are never fully independent of biological state. We can diagnose cell type loss by looking for systematic differences in gene expression between the discarded and retained cells.

Show code

lost <- calculateAverage(counts(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, !keep])

kept <- calculateAverage(counts(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, keep])

library(edgeR)

logged <- cpm(cbind(lost, kept), log = TRUE, prior.count = 2)

logFC <- logged[, 1] - logged[, 2]

abundance <- rowMeans(logged)

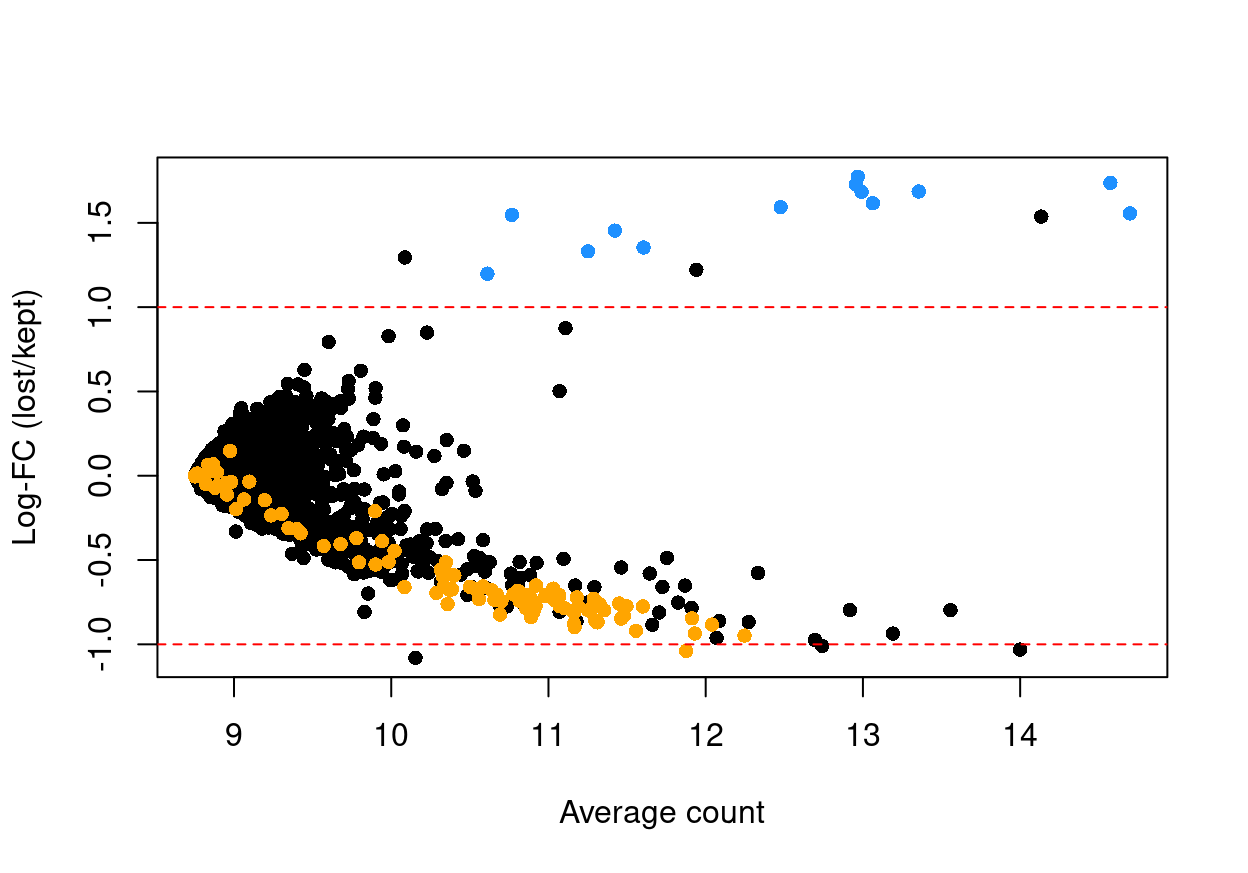

Figure 5 shows the result of this analysis, highlighting that the systematically upregulated genes are mitochondrial transcripts and that those systematically downregulated genes are largely ribosomal protein genes. This suggests that the QC step did not inadvertently filter out an entire biologically relevant subpopulation.

Show code

is_mito <- rownames(sce) %in% mito_set

is_ribo <- rownames(sce) %in% ribo_set

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))

plot(

abundance,

logFC,

xlab = "Average count",

ylab = "Log-FC (lost/kept)",

pch = 16)

points(

abundance[is_mito],

logFC[is_mito],

col = "dodgerblue",

pch = 16,

cex = 1)

points(

abundance[is_ribo],

logFC[is_ribo],

col = "orange",

pch = 16,

cex = 1)

abline(h = c(-1, 1), col = "red", lty = 2)

Figure 5: Log-fold change in expression in the discarded cells compared to the retained cells. Each point represents a gene with mitochondrial transcripts in blue and ribosomal protein genes in orange. Dashed red lines indicate $|logFC| = 1

Show code

library(Glimma)

glMDPlot(

x = data.frame(abundance = abundance, logFC = logFC),

xval = "abundance",

yval = "logFC",

counts = cbind(lost, kept),

anno = cbind(

as.data.frame(rowData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)),

data.frame(

GeneID = rownames(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)),

display.columns = c("Symbol", "ID", "CHR"),

groups = factor(c("lost", "kept")),

samples = c("lost", "kept"),

status = unname(ifelse(is_mito, 1, ifelse(is_ribo, -1, 0))),

transform = FALSE,

main = "lost vs. kept",

side.ylab = "Average count",

cols = c("orange", "black", "dodgerBlue"),

path = here("output"),

html = "qc-md-plot",

launch = FALSE)

If the discarded pool is enriched for a certain cell type, we should observe increased expression of the corresponding marker genes.

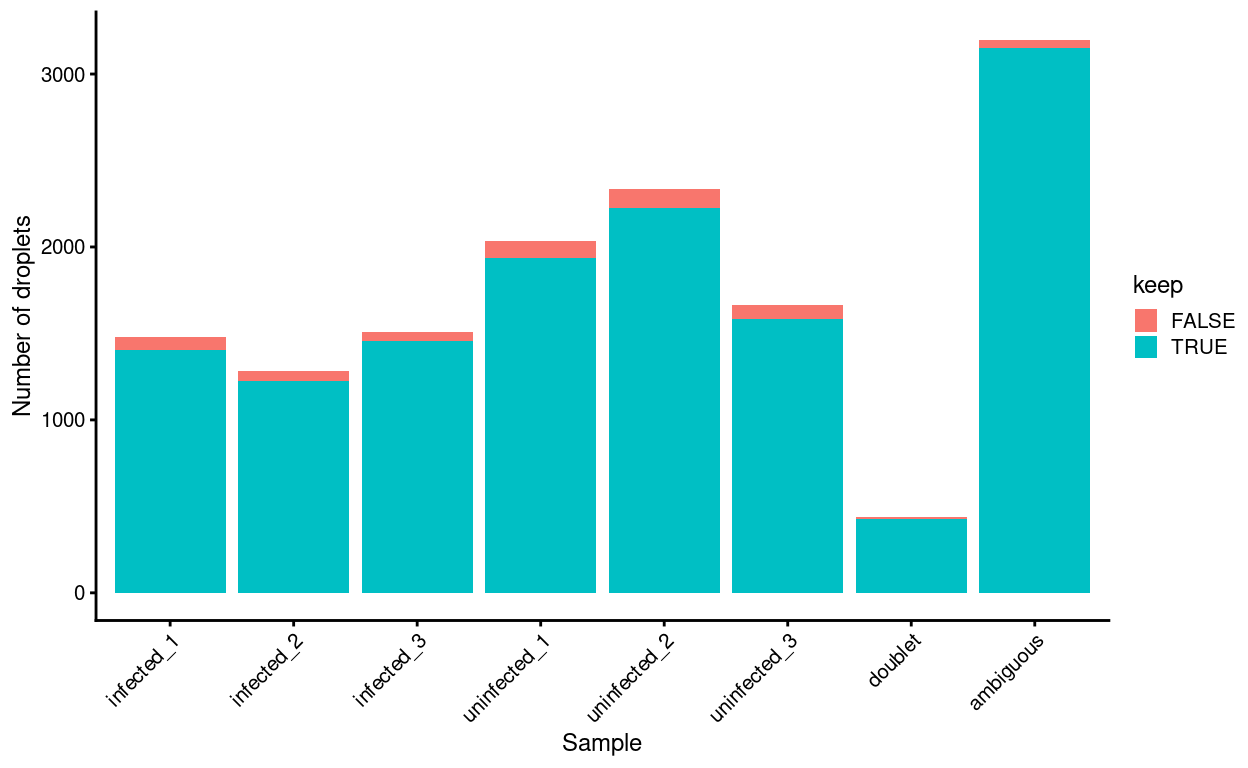

Another concern is whether the cells removed during QC preferentially derive from particular experimental groups. Reassuringly, Figure 6 shows that this is not the case.

Show code

ggplot(

as.data.frame(colData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, c("Sample", "keep")])) +

geom_bar(aes(x = Sample, fill = keep)) +

ylab("Number of droplets") +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 9) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

Figure 6: Droplets removed during QC, stratified by Sample.

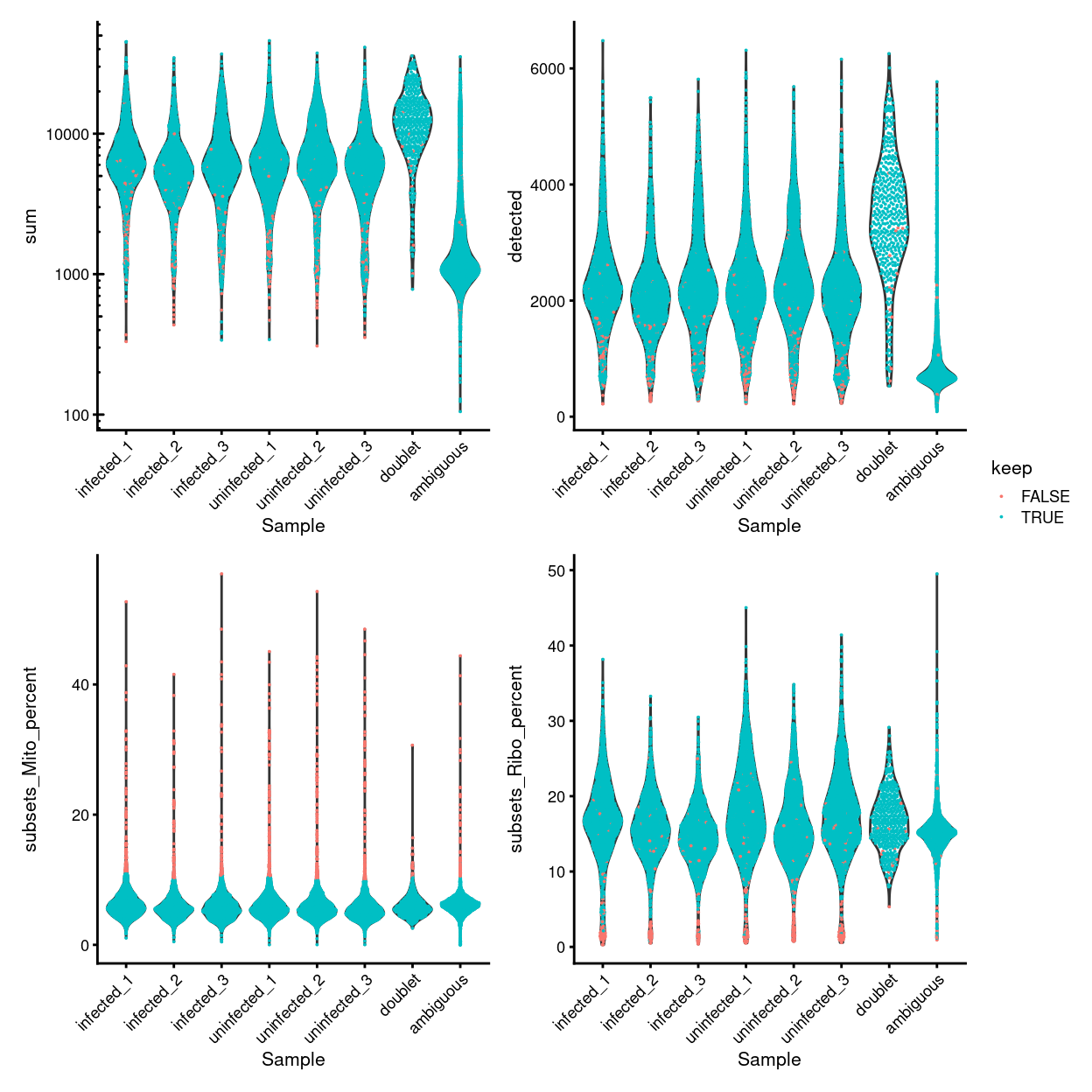

Finally, Figure 7 compares the QC metrics of the discarded and retained droplets.

Show code

p1 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, c("Sample", "sum", "keep")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = sum)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01, aes(colour = keep)) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

scale_y_log10() +

annotation_logticks(

sides = "l",

short = unit(0.03, "cm"),

mid = unit(0.06, "cm"),

long = unit(0.09, "cm"))

p2 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, c("Sample", "detected", "keep")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = detected)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01, aes(colour = keep)) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p3 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, c("Sample", "subsets_Mito_percent", "keep")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = subsets_Mito_percent)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01, aes(colour = keep)) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p4 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce_pre_QC_outlier_removal)[, c("Sample", "subsets_Ribo_percent", "keep")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = subsets_Ribo_percent)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01, aes(colour = keep)) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p1 + p2 + p3 + p4 + plot_layout(guides = "collect")

Figure 7: Distribution of QC metrics for each plate in the dataset. Each point represents a cell and is colored according to whether it was discarded during the QC process. Note that a cell will only be kept if it passes the relevant threshold for all four QC metrics.

Summary

We had already removed droplets that have unusually small library sizes or number of genes detected by the process of identifying empty droplets. We have now further removed droplets whose mitochondrial proportions we deem to be an outlier.

For the time being, we opt to retain the Unknown droplets because these may allow us to identify a subpopulation of cells that are not captured by hashing.

To conclude, Figure 8 shows that following QC that most samples have similar QC metrics, as is to be expected, and Figure 9 summarises the experimental design following QC.

Show code

p1 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "sum")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = sum, colour = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

scale_y_log10() +

annotation_logticks(

sides = "l",

short = unit(0.03, "cm"),

mid = unit(0.06, "cm"),

long = unit(0.09, "cm"))

p2 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "detected")]),

aes(x = Sample, y = detected, colour = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p3 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "subsets_Mito_percent")]),

aes(

x = Sample,

y = subsets_Mito_percent,

colour = Treatment,

fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p4 <- ggplot(

data = as.data.frame(

colData(sce)[, c("Sample", "Treatment", "subsets_Ribo_percent")]),

aes(

x = Sample,

y = subsets_Ribo_percent,

colour = Treatment,

fill = Treatment)) +

geom_violin(scale = "width", width = 0.8, alpha = 0.2) +

ggbeeswarm::geom_quasirandom(size = 0.01) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 8) +

scale_colour_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p1 + p2 + p3 + p4 + plot_layout(guides = "collect")

Figure 8: Distributions of various QC metrics for all cells in the dataset passing QC. This includes the library sizes and proportion of reads mapped to mitochondrial genes.

Show code

plot_grid(

ggplot(as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Treatment", "Sample")])) +

geom_bar(

aes(x = Treatment, fill = Sample),

position = position_fill(reverse = TRUE)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Frequency") +

scale_fill_manual(values = sample_colours) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10),

ggplot(as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, c("Treatment", "Sample")])) +

geom_bar(aes(x = Treatment, fill = Treatment)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Number of droplets") +

scale_fill_manual(values = treatment_colours) +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10),

align = "h",

ncol = 2)

Figure 9: Breakdown of the samples following QC.

Examining gene-level metrics

Inspecting the most highly expressed genes

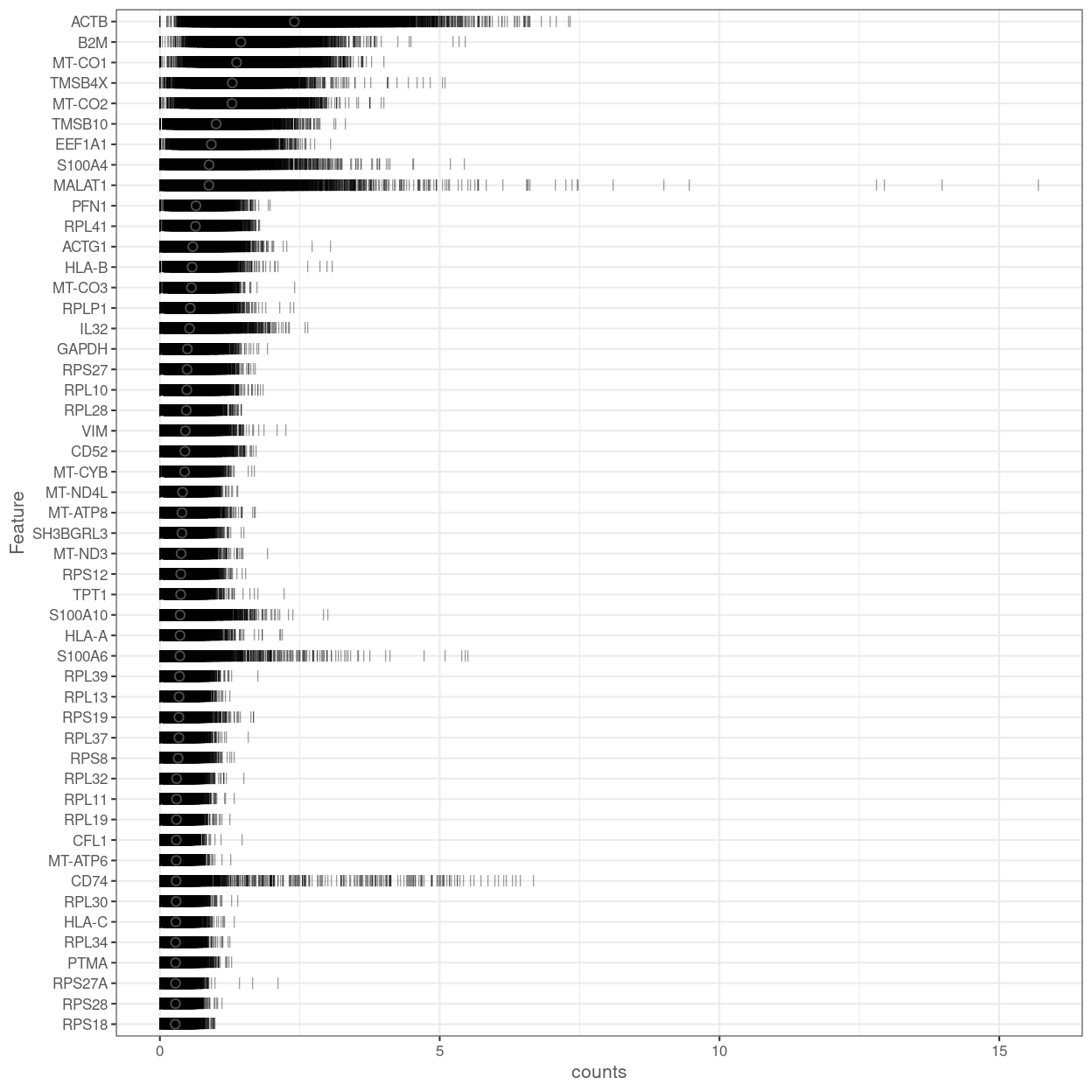

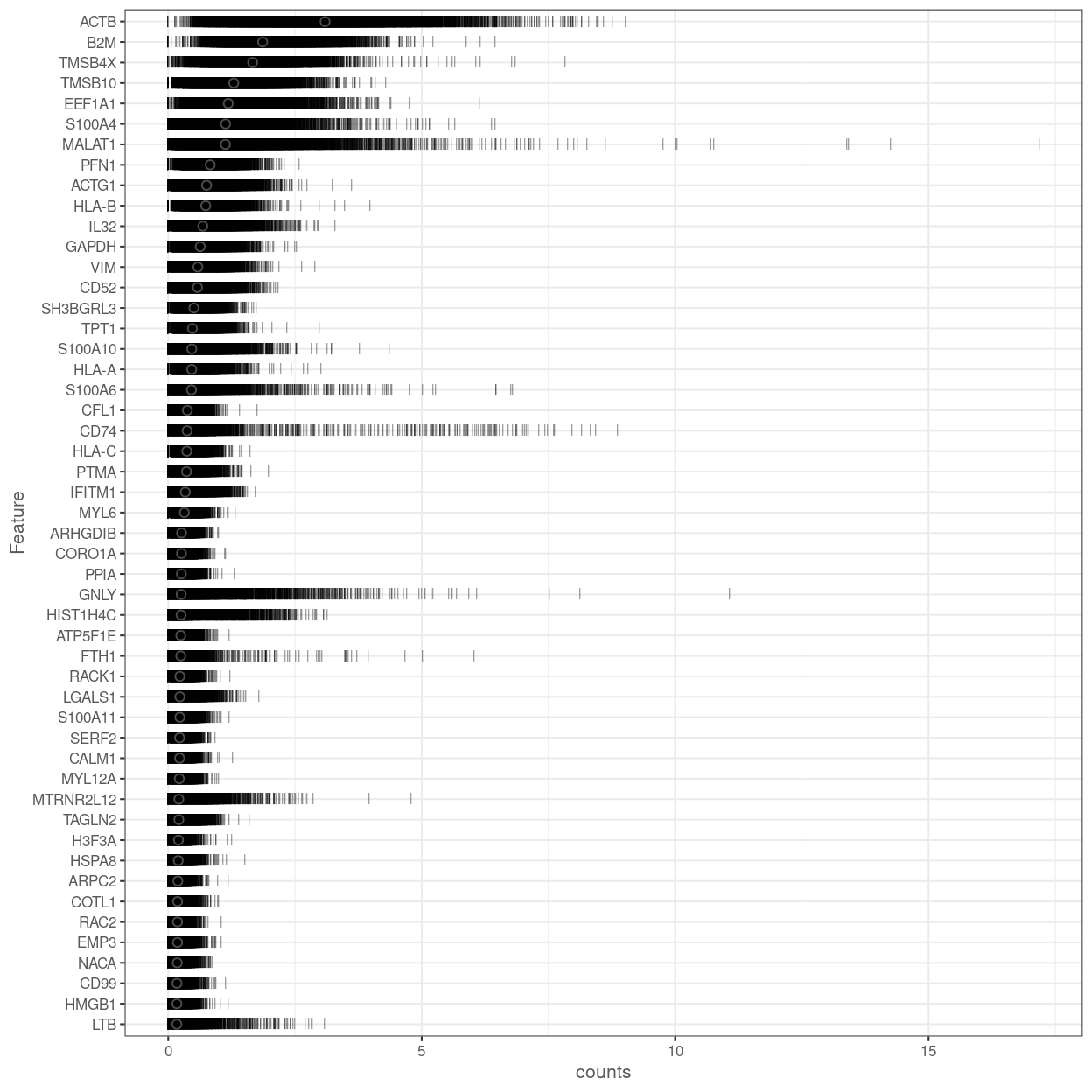

Figure 10 shows the most highly expressed genes across the cell population in the combined data set. Some of them are mitochondrial genes, matching what we’ve already seen in the QC metrics, and ribosomal protein genes, which commonly are amongst the most highly expressed genes in scRNA-seq data.

Show code

plotHighestExprs(sce, n = 50)

Figure 10: Percentage of total counts assigned to the top 50 most highly-abundant features in the combined data set. For each feature, each bar represents the percentage assigned to that feature for a single cell, while the circle represents the average across all cells.

Figure 11 shows the most highly expressed endogenous genes after excluding the mitochondrial and ribosomal protein genes.

Show code

plotHighestExprs(sce[!rownames(sce) %in% union(mito_set, ribo_set), ], n = 50)

Figure 11: Percentage of total counts assigned to the top 50 most highly-abundant features in the combined data set. For each feature, each bar represents the percentage assigned to that feature for a single cell, while the circle represents the average across all cells. Bars are coloured by the total number of expressed features in each cell, while circles are coloured according to whether the feature is labelled as a control feature.

Filtering out low-abundance genes

Low-abundance genes are problematic as zero or near-zero counts do not contain much information for reliable statistical inference (Bourgon, Gentleman, and Huber 2010). These genes typically do not provide enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis during testing, yet they still increase the severity of the multiple testing correction. In addition, the discreteness of the counts may interfere with statistical procedures, e.g., by compromising the accuracy of continuous approximations. Thus, low-abundance genes are often removed in many RNA-seq analysis pipelines before the application of downstream methods.

The ‘optimal’ choice of filtering strategy depends on the downstream application. A more aggressive filter is usually required to remove discreteness (e.g., for normalization) compared to that required for removing underpowered tests. For hypothesis testing, the filter statistic should also be independent of the test statistic under the null hypothesis. Thus, we (or the relevant function) will filter at each step as needed, rather than applying a single filter for the entire analysis.

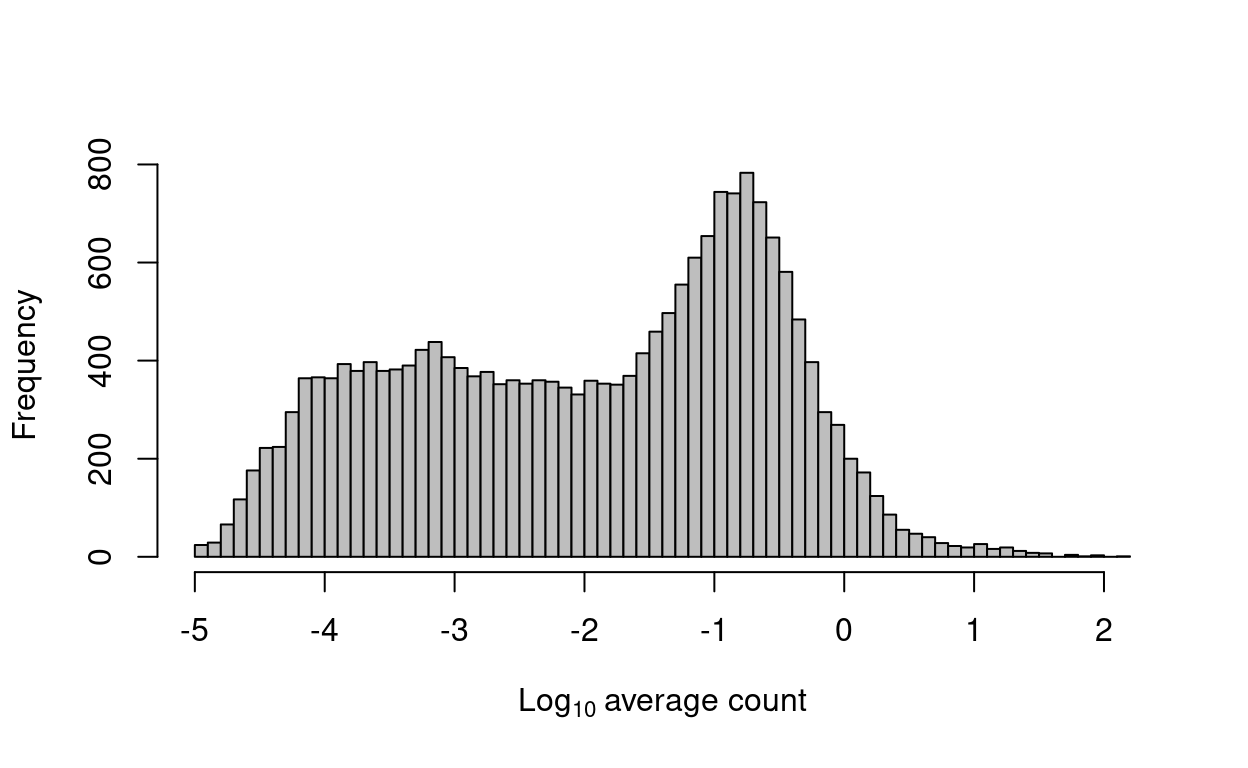

Several metrics can be used to define low-abundance genes. The most obvious is the average count for each gene, computed across all cells in the data set. We typically observe a peak of moderately expressed genes following a plateau of lowly expressed genes (Figure 12).

Show code

ave_counts <- calculateAverage(sce)

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))

hist(

x = log10(ave_counts),

breaks = 100,

main = "",

col = "grey",

xlab = expression(Log[10] ~ "average count"))

Figure 12: Histogram of log-average counts for all genes in the combined data set.

Show code

to_keep <- ave_counts > 0

sce <- sce[to_keep, ]

We remove 12936 genes that are not expressed in any cell. Such genes provide no information and would be removed by any filtering strategy. We retain 20602 for downstream analysis.

Normalization of cell-specific biases

Read counts are subject to differences in capture efficiency and sequencing depth between cells (Stegle, Teichmann, and Marioni 2015). Normalization is required to eliminate these cell-specific biases prior to downstream quantitative analyses. This is often done by assuming that most genes are not differentially expressed (DE) between cells. Any systematic difference in count size across the non-DE majority of genes between two cells is assumed to represent bias and is removed by scaling. More specifically, ‘size factors’ are calculated that represent the extent to which counts should be scaled in each library.

Using the deconvolution method to deal with zero counts

Size factors can be computed with several different approaches, e.g., using the estimateSizeFactorsFromMatrix function in the DESeq2 package (Anders and Huber 2010; Love, Huber, and Anders 2014), or with the calcNormFactors function (Robinson and Oshlack 2010) in the edgeR package. However, single-cell data can be problematic for these bulk data-based methods due to the dominance of low and zero counts. To overcome this, we pool counts from many cells to increase the count size for accurate size factor estimation (A. T. Lun, Bach, and Marioni 2016). Pool-based size factors are then ‘deconvolved’ into cell-based factors for cell-specific normalization. This removes scaling biases associated with cell-specific differences in capture efficiency, sequencing depth and composition biases.

Show code

library(scran)

set.seed(943488)

clusters <- quickCluster(sce, BSPARAM = BiocSingular::IrlbaParam())

round(prop.table(table(clusters, sce$batch), 1), 2)

sce <- computeSumFactors(sce, clusters = clusters, min.mean = 0.1)

summary(sizeFactors(sce))

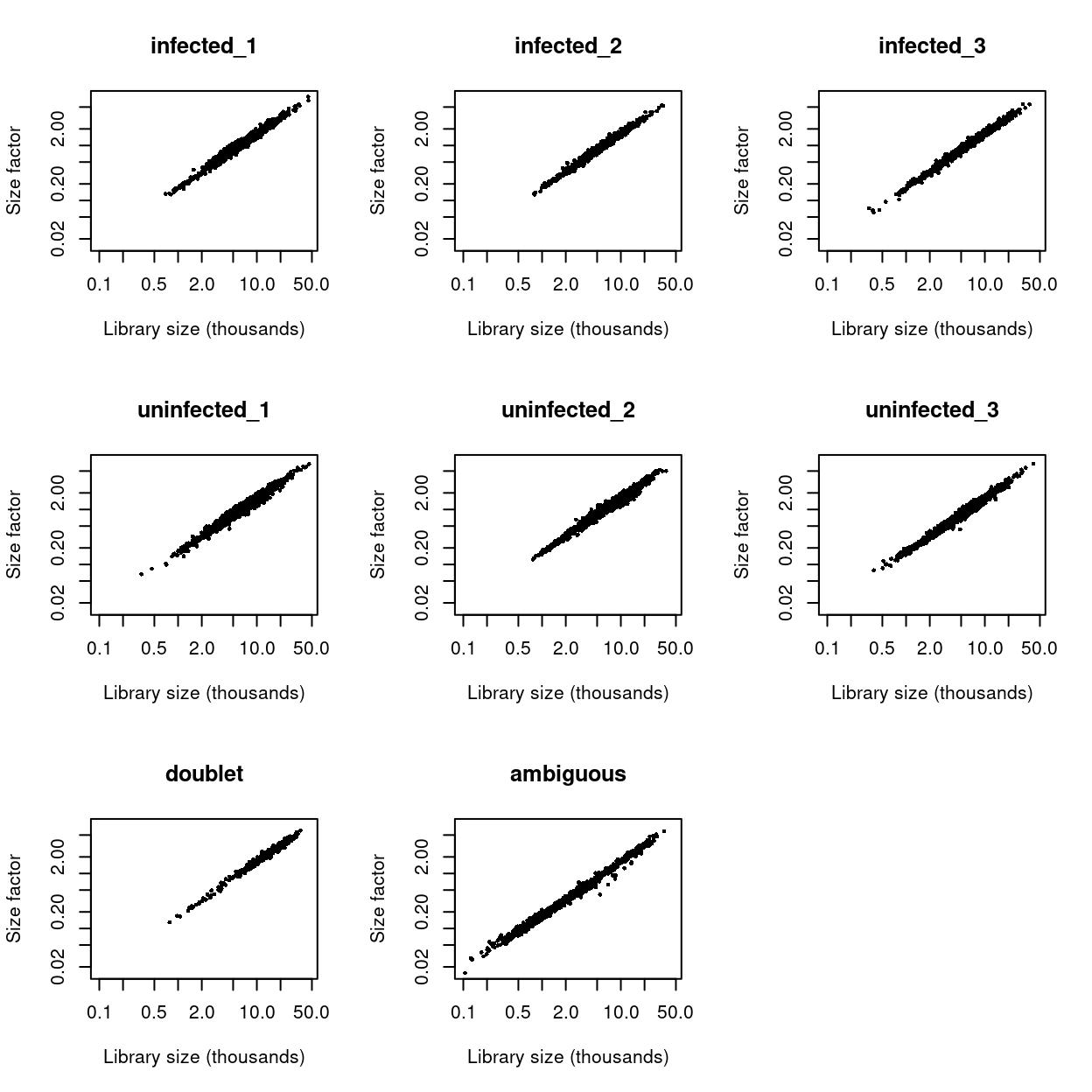

We check that the size factors are roughly aligned with the total library sizes (Figure 13). Deviations from the diagonal correspond to composition biases due to differential expression between cell subpopulations.

Show code

xlim <- c(0.1, max(sce$sum) / 1e3)

ylim <- range(sizeFactors(sce))

par(mfrow = c(3, 3))

lapply(levels(sce$Sample), function(s) {

sce <- sce[, sce$Sample == s]

plot(

x = sce$sum / 1e3,

y = sizeFactors(sce),

log = "xy",

xlab = "Library size (thousands)",

ylab = "Size factor",

xlim = xlim,

ylim = ylim,

main = s,

pch = 16,

cex = 0.5)

})

Figure 13: Size factors from deconvolution, plotted against library sizes for all cells in each dataset. Axes are shown on a log-scale.

Applying the size factors to normalize gene expression

The count data are used to compute normalized log-expression values for use in downstream analyses. Each value is defined as the log2-ratio of each count to the size factor for the corresponding cell, after adding a prior count of 1 to avoid undefined values at zero counts. Division by the size factor ensures that any cell-specific biases are removed.

Show code

# NOTE: No need for multiBatchNorm() since the size factors were computed

# jointly using all samples.

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

Feature selection

Motivation

We often use scRNA-seq data in exploratory analyses to characterize heterogeneity across cells. Procedures like dimensionality reduction and clustering compare cells based on their gene expression profiles, which involves aggregating per-gene differences into a single (dis)similarity metric between a pair of cells. The choice of genes to use in this calculation has a major impact on the behaviour of the metric and the performance of downstream methods. We want to select genes that contain useful information about the biology of the system while removing genes that contain random noise. This aims to preserve interesting biological structure without the variance that obscures that structure. It also reduces the size of the dataset to improve computational efficiency of later steps.

Quantifying per-gene variation

Variance of the log-counts

The simplest approach to quantifying per-gene variation is to simply compute the variance of the log-normalized expression values (referred to as “log-counts” for simplicity) for each gene across all cells in the population (A. T. L. Lun, McCarthy, and Marioni 2016). This has an advantage in that the feature selection is based on the same log-values that are used for later downstream steps. In particular, genes with the largest variances in log-values will contribute the most to the Euclidean distances between cells. By using log-values here, we ensure that our quantitative definition of heterogeneity is consistent throughout the entire analysis.

Calculation of the per-gene variance is simple but feature selection requires modelling of the mean-variance relationship.

Quantifying technical noise

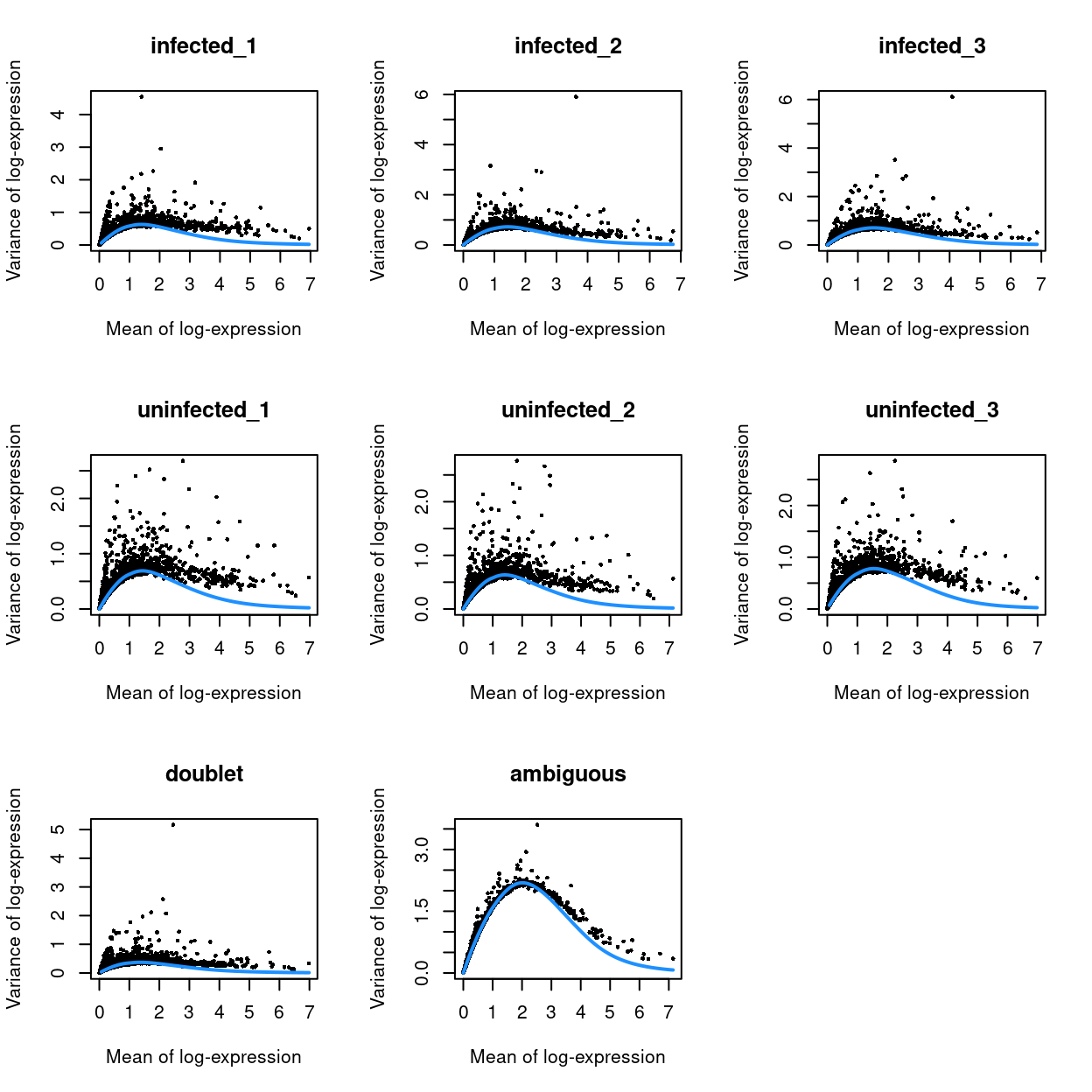

To account for the mean-variance relationship, we fit a trend to the variance with under the assumption of Poisson variation. UMI counts typically exhibit near-Poisson variation if we only consider technical noise from library preparation and sequencing.

Accounting for blocking factors

Data containing multiple batches will often exhibit batch effects. We are usually not interested in highly variable genes (HVGs) that are driven by batch effects. Rather, we want to focus on genes that are highly variable within each batch. This is naturally achieved by performing trend fitting and variance decomposition separately for each batch.

Show code

set.seed(2861)

var_fit <- modelGeneVarByPoisson(sce, block = sce$batch)

The use of a batch-specific trend fit is useful as it accommodates differences in the mean-variance trends between batches. This is especially important if batches exhibit systematic technical differences, e.g., differences in coverage.

Figure 14 visualizes the quality of the batch-specific trend fits and highlights the need for batch-specific estimates of these fits. The analysis of each batch yields estimates of the biological and technical components for each gene, which are averaged across batches.

Show code

par(mfrow = c(3, 3))

blocked.stats <- var_fit$per.block

for (i in colnames(blocked.stats)) {

current <- blocked.stats[[i]]

plot(

current$mean,

current$total,

main = i,

pch = 16,

cex = 0.5,

xlab = "Mean of log-expression",

ylab = "Variance of log-expression")

curfit <- metadata(current)

curve(curfit$trend(x), col = "dodgerblue", add = TRUE, lwd = 2)

}

Figure 14: Variance in the data set as a function of the mean after blocking. Each plot represents the results for a single batch, each point represents a gene (black) and the blue line represents the Poisson trend.

Selecting highly variable genes (HVGs)

Once we have quantified the per-gene variation, the next step is to select the subset of HVGs to use in downstream analyses. A larger subset will reduce the risk of discarding interesting biological signal by retaining more potentially relevant genes, at the cost of increasing noise from irrelevant genes that might obscure said signal. It is difficult to determine the optimal trade-off for any given application as noise in one context may be useful signal in another. For example, heterogeneity in T cell activation responses is an interesting phenomena but may be irrelevant noise in studies that only care about distinguishing the major immunophenotypes.

We opt to only remove the obviously uninteresting genes with variances below the trend. By doing so, we avoid the need to make any judgement calls regarding what level of variation is interesting enough to retain. This approach represents one extreme of the bias-variance trade-off where bias is minimized at the cost of maximizing noise.

Show code

hvg <- getTopHVGs(var_fit, var.threshold = 0)

Summary

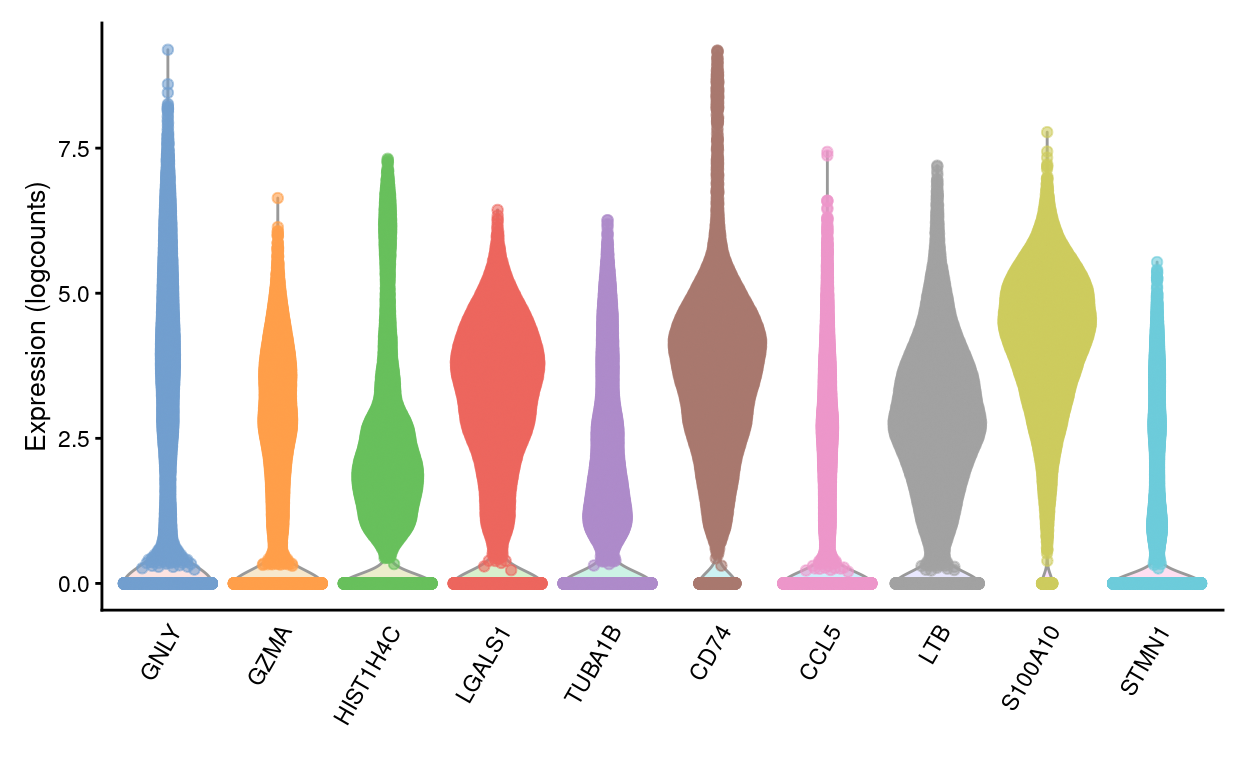

We are left with 15193 HVGs by this approach5. Figure 15 shows the expression of the top-10 HVGs.

Show code

plotExpression(object = sce, features = hvg[1:10])

Figure 15: Violin plots of normalized log-expression values for the top-10 HVGs. Each point represents the log-expression value in a single cell.

Dimensionality reduction

Many scRNA-seq analysis procedures involve comparing cells based on their expression values across multiple genes. In these applications, each individual gene represents a dimension of the data. If we had a scRNA-seq data set with two genes, we could make a two-dimensional plot where each axis represents the expression of one gene and each point in the plot represents a cell. Dimensionality reduction extends this idea to data sets with thousands of genes where each cell’s expression profile defines its location in the high-dimensional expression space.

As the name suggests, dimensionality reduction aims to reduce the number of separate dimensions in the data. This is possible because different genes are correlated if they are affected by the same biological process. Thus, we do not need to store separate information for individual genes, but can instead compress multiple features into a single dimension. This reduces computational work in downstream analyses, as calculations only need to be performed for a few dimensions rather than thousands of genes; reduces noise by averaging across multiple genes to obtain a more precise representation of the patterns in the data; and enables effective plotting of the data, for those of us who are not capable of visualizing more than 3 dimensions.

Principal component analysis

Principal components analysis (PCA) discovers axes in high-dimensional space that capture the largest amount of variation. In PCA, the first axis (or “principal component”, PC) is chosen such that it captures the greatest variance across cells. The next PC is chosen such that it is orthogonal to the first and captures the greatest remaining amount of variation, and so on.

By definition, the top PCs capture the dominant factors of heterogeneity in the data set. Thus, we can perform dimensionality reduction by restricting downstream analyses to the top PCs. This strategy is simple, highly effective and widely used throughout the data sciences.

When applying PCA to scRNA-seq data, our assumption is that biological processes affect multiple genes in a coordinated manner. This means that the earlier PCs are likely to represent biological structure as more variation can be captured by considering the correlated behaviour of many genes. By comparison, random technical or biological noise is expected to affect each gene independently. There is unlikely to be an axis that can capture random variation across many genes, meaning that noise should mostly be concentrated in the later PCs. This motivates the use of the earlier PCs in our downstream analyses, which concentrates the biological signal to simultaneously reduce computational work and remove noise.

We perform the PCA on the log-normalized expression values. PCA is generally robust to random noise but an excess of it may cause the earlier PCs to capture noise instead of biological structure. This effect can be avoided - or at least mitigated - by restricting the PCA to a subset of HVGs, as done in Feature selection.

The choice of the number of PCs is a decision that is analogous to the choice of the number of HVGs to use. Using more PCs will avoid discarding biological signal in later PCs, at the cost of retaining more noise.

We use the strategy of retaining all PCs until the percentage of total variation explained reaches some threshold. We derive a suitable value for this threshold by calculating the proportion of variance in the data that is attributed to the biological component. This is done using the the variance modelling results from Quantifying per-gene variation.

Show code

set.seed(67726)

sce <- denoisePCA(sce, var_fit, subset.row = hvg)

This retains 38 dimensions, which represents the lower bound on the number of PCs required to retain all biological variation. Any fewer PCs will definitely discard some aspect of biological signal6. This approach provides a reasonable choice when we want to retain as much signal as possible while still removing some noise.

Dimensionality reduction for visualization

We use the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) method (McInnes, Healy, and Melville 2018) to perform further dimensionality reduction for visualization.

Show code

library(uwot)

set.seed(853)

sce <- runUMAP(sce, dimred = "PCA")

umap_df <- cbind(

data.frame(

x = reducedDim(sce, "UMAP")[, 1],

y = reducedDim(sce, "UMAP")[, 2]),

as.data.frame(colData(sce)[, !colnames(colData(sce)) %in% c("TRA", "TRB")]))

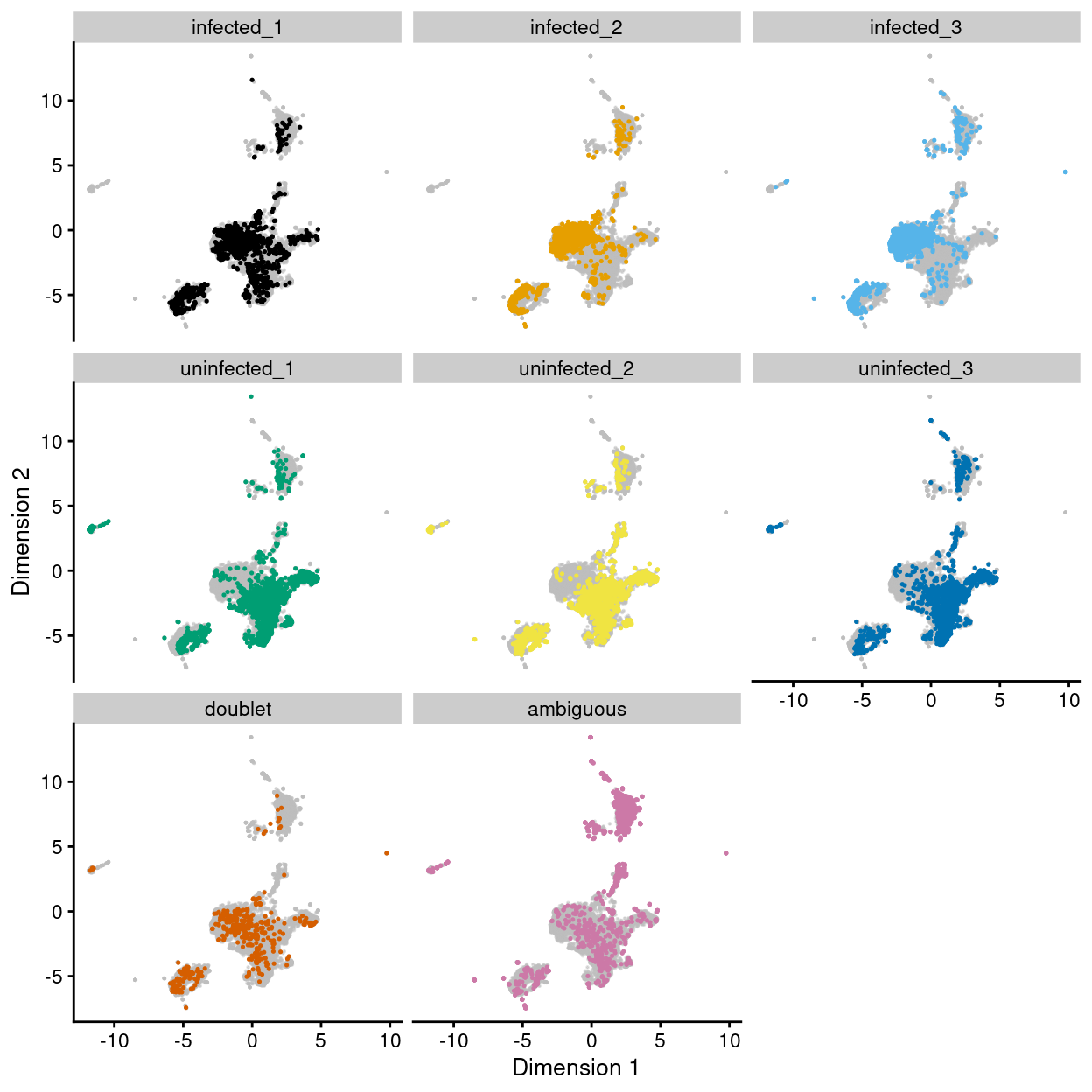

Figure 16 visualizes the droplets using the UMAP co-ordinates.

Show code

bg <- dplyr::select(umap_df, -Sample)

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y), data = umap_df) +

geom_point(data = bg, colour = scales::alpha("grey", 0.5), size = 0.125) +

geom_point(aes(colour = Sample), alpha = 1, size = 0.25) +

scale_fill_manual(values = sample_colours, name = "HTO") +

scale_colour_manual(values = sample_colours, name = "HTO") +

theme_cowplot(font_size = 10) +

xlab("Dimension 1") +

ylab("Dimension 2") +

facet_wrap(~ Sample, ncol = 3) +

guides(colour = FALSE)

Figure 16: UMAP plot of the dataset. Each point represents a droplets and is coloured by Sample. Each panel highlights droplets from a particular sample.

Summary

Although Figure 16 is only a preliminary summary of the data, there are few points worth highlighting:

- In terms of UMAP co-ordinates, there are some visual differences between

InfectedandUninfectedsamples that are consistent across replicates. - The

Unknowndroplets are somewhat localised on the UMAP plot but these regions also contain droplets confidently assigned to a sample.

Concluding remarks

The processed SingleCellExperiment object is available (see data/SCEs/C057_Cooney.preprocessed.SCE.rds). This will be used in downstream analyses, e.g., selecting biologically relevant cells.

Additional information

The following are available on request:

- Full CSV tables of any data presented.

- PDF/PNG files of any static plots.

Session info

Show code

sessioninfo::session_info()

─ Session info ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────

setting value

version R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10)

os CentOS Linux 7 (Core)

system x86_64, linux-gnu

ui X11

language (EN)

collate en_US.UTF-8

ctype en_US.UTF-8

tz Australia/Melbourne

date 2021-04-01

─ Packages ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

! package * version date lib

P annotate 1.68.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P AnnotationDbi * 1.52.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P AnnotationFilter * 1.14.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P AnnotationHub * 2.22.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P askpass 1.1 2019-01-13 [?]

P assertthat 0.2.1 2019-03-21 [?]

P beachmat 2.6.4 2020-12-20 [?]

P beeswarm 0.2.3 2016-04-25 [?]

P Biobase * 2.50.0 2020-10-27 [?]

BiocFileCache * 1.14.0 2020-10-27 [1]

BiocGenerics * 0.36.0 2020-10-27 [1]

P BiocManager 1.30.10 2019-11-16 [?]

P BiocNeighbors 1.8.2 2020-12-07 [?]

BiocParallel * 1.24.1 2020-11-06 [1]

P BiocSingular 1.6.0 2020-10-27 [?]

BiocStyle * 2.18.1 2020-11-24 [1]

BiocVersion 3.12.0 2020-04-27 [1]

P biomaRt 2.46.3 2021-02-09 [?]

P Biostrings 2.58.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P bit 4.0.4 2020-08-04 [?]

P bit64 4.0.5 2020-08-30 [?]

P bitops 1.0-6 2013-08-17 [?]

P blob 1.2.1 2020-01-20 [?]

P bluster 1.0.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P bslib 0.2.4 2021-01-25 [?]

P cachem 1.0.4 2021-02-13 [?]

P cli 2.3.1 2021-02-23 [?]

P codetools 0.2-18 2020-11-04 [?]

P colorspace 2.0-0 2020-11-11 [?]

P cowplot * 1.1.1 2020-12-30 [?]

P crayon 1.4.1 2021-02-08 [?]

P curl 4.3 2019-12-02 [?]

P DBI 1.1.1 2021-01-15 [?]

P dbplyr * 2.1.0 2021-02-03 [?]

P DelayedArray 0.16.2 2021-02-26 [?]

P DelayedMatrixStats 1.12.3 2021-02-03 [?]

P DESeq2 1.30.1 2021-02-19 [?]

P digest 0.6.27 2020-10-24 [?]

P distill 1.2 2021-01-13 [?]

P downlit 0.2.1 2020-11-04 [?]

P dplyr 1.0.4 2021-02-02 [?]

P dqrng 0.2.1 2019-05-17 [?]

P edgeR * 3.32.1 2021-01-14 [?]

P ellipsis 0.3.1 2020-05-15 [?]

P ensembldb * 2.14.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P evaluate 0.14 2019-05-28 [?]

P fansi 0.4.2 2021-01-15 [?]

P farver 2.1.0 2021-02-28 [?]

P fastmap 1.1.0 2021-01-25 [?]

P genefilter 1.72.1 2021-01-21 [?]

P geneplotter 1.68.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P generics 0.1.0 2020-10-31 [?]

P GenomeInfoDb * 1.26.2 2020-12-08 [?]

GenomeInfoDbData 1.2.4 2021-02-04 [1]

P GenomicAlignments 1.26.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P GenomicFeatures * 1.42.1 2020-11-12 [?]

P GenomicRanges * 1.42.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P ggbeeswarm 0.6.0 2017-08-07 [?]

P ggplot2 * 3.3.3 2020-12-30 [?]

P Glimma * 2.0.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P glue 1.4.2 2020-08-27 [?]

P GO.db * 3.12.1 2020-11-04 [?]

P graph 1.68.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P gridExtra 2.3 2017-09-09 [?]

P gtable 0.3.0 2019-03-25 [?]

P here * 1.0.1 2020-12-13 [?]

P highr 0.8 2019-03-20 [?]

P hms 1.0.0 2021-01-13 [?]

P Homo.sapiens * 1.3.1 2020-07-25 [?]

P htmltools 0.5.1.1 2021-01-22 [?]

P htmlwidgets 1.5.3 2020-12-10 [?]

P httpuv 1.5.5 2021-01-13 [?]

P httr 1.4.2 2020-07-20 [?]

P igraph 1.2.6 2020-10-06 [?]

P interactiveDisplayBase 1.28.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P IRanges * 2.24.1 2020-12-12 [?]

P irlba 2.3.3 2019-02-05 [?]

P janitor * 2.1.0 2021-01-05 [?]

P jquerylib 0.1.3 2020-12-17 [?]

P jsonlite 1.7.2 2020-12-09 [?]

P knitr 1.31 2021-01-27 [?]

P labeling 0.4.2 2020-10-20 [?]

P later 1.1.0.1 2020-06-05 [?]

P lattice 0.20-41 2020-04-02 [?]

P lazyeval 0.2.2 2019-03-15 [?]

P lifecycle 1.0.0 2021-02-15 [?]

limma * 3.46.0 2020-10-27 [1]

P locfit 1.5-9.4 2020-03-25 [?]

P lubridate 1.7.10 2021-02-26 [?]

P magrittr 2.0.1 2020-11-17 [?]

P Matrix * 1.3-2 2021-01-06 [?]

MatrixGenerics * 1.2.1 2021-01-30 [1]

P matrixStats * 0.58.0 2021-01-29 [?]

P memoise 2.0.0 2021-01-26 [?]

P mime 0.10 2021-02-13 [?]

P msigdbr * 7.2.1 2020-10-02 [?]

P munsell 0.5.0 2018-06-12 [?]

P openssl 1.4.3 2020-09-18 [?]

P org.Hs.eg.db * 3.12.0 2020-10-20 [?]

P OrganismDbi * 1.32.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P patchwork * 1.1.1 2020-12-17 [?]

P pillar 1.5.0 2021-02-22 [?]

P pkgconfig 2.0.3 2019-09-22 [?]

P prettyunits 1.1.1 2020-01-24 [?]

P progress 1.2.2 2019-05-16 [?]

P promises 1.2.0.1 2021-02-11 [?]

ProtGenerics 1.22.0 2020-10-27 [1]

P purrr 0.3.4 2020-04-17 [?]

P R6 2.5.0 2020-10-28 [?]

P rappdirs 0.3.3 2021-01-31 [?]

P RBGL 1.66.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P RColorBrewer 1.1-2 2014-12-07 [?]

P Rcpp 1.0.6 2021-01-15 [?]

P RcppAnnoy 0.0.18 2020-12-15 [?]

P RCurl 1.98-1.2 2020-04-18 [?]

P rlang 0.4.10 2020-12-30 [?]

P rmarkdown * 2.7 2021-02-19 [?]

P rprojroot 2.0.2 2020-11-15 [?]

P Rsamtools 2.6.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P RSpectra 0.16-0 2019-12-01 [?]

P RSQLite 2.2.3 2021-01-24 [?]

P rsvd 1.0.3 2020-02-17 [?]

P rtracklayer 1.50.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P S4Vectors * 0.28.1 2020-12-09 [?]

P sass 0.3.1 2021-01-24 [?]

P scales 1.1.1 2020-05-11 [?]

P scater * 1.18.6 2021-02-26 [?]

P scran * 1.18.5 2021-02-04 [?]

P scuttle 1.0.4 2020-12-17 [?]

P sessioninfo 1.1.1 2018-11-05 [?]

P shiny 1.6.0 2021-01-25 [?]

P SingleCellExperiment * 1.12.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P snakecase 0.11.0 2019-05-25 [?]

P sparseMatrixStats 1.2.1 2021-02-02 [?]

P statmod 1.4.35 2020-10-19 [?]

P stringi 1.5.3 2020-09-09 [?]

P stringr 1.4.0 2019-02-10 [?]

P SummarizedExperiment * 1.20.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P survival 3.2-7 2020-09-28 [?]

P tibble 3.1.0 2021-02-25 [?]

P tidyselect 1.1.0 2020-05-11 [?]

P TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene * 3.2.2 2020-07-25 [?]

P utf8 1.1.4 2018-05-24 [?]

P uwot * 0.1.10 2020-12-15 [?]

P vctrs 0.3.6 2020-12-17 [?]

P vipor 0.4.5 2017-03-22 [?]

P viridis 0.5.1 2018-03-29 [?]

P viridisLite 0.3.0 2018-02-01 [?]

P withr 2.4.1 2021-01-26 [?]

P xfun 0.21 2021-02-10 [?]

P XML 3.99-0.5 2020-07-23 [?]

P xml2 1.3.2 2020-04-23 [?]

P xtable 1.8-4 2019-04-21 [?]

P XVector 0.30.0 2020-10-27 [?]

P yaml 2.2.1 2020-02-01 [?]

P zlibbioc 1.36.0 2020-10-27 [?]

source

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.2)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.3)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

CRAN (R 4.0.0)

Bioconductor

[1] /stornext/Projects/score/Analyses/C057_Cooney/renv/library/R-4.0/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

[2] /tmp/RtmpNjHKzV/renv-system-library

[3] /stornext/System/data/apps/R/R-4.0.3/lib64/R/library

P ── Loaded and on-disk path mismatch.Anders, S., and W. Huber. 2010. “Differential Expression Analysis for Sequence Count Data.” Genome Biol. 11 (10): R106. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20979621.

Bourgon, R., R. Gentleman, and W. Huber. 2010. “Independent Filtering Increases Detection Power for High-Throughput Experiments.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (21): 9546–51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20460310.

Love, M. I., W. Huber, and S. Anders. 2014. “Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for Rna-Seq Data with Deseq2.” Genome Biol. 15 (12): 550. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25516281.

Lun, A. T., K. Bach, and J. C. Marioni. 2016. Genome Biol. 17 (April): 75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27122128.

Lun, A. T. L., D. J. McCarthy, and J. C. Marioni. 2016. “A Step-by-Step Workflow for Low-Level Analysis of Single-Cell RNA-seq Data.” F1000Res. 5 (August).

McInnes, Leland, John Healy, and James Melville. 2018. “UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction,” February. http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426.

Robinson, M. D., and A. Oshlack. 2010. “A Scaling Normalization Method for Differential Expression Analysis of Rna-Seq Data.” Genome Biol. 11 (3): R25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20196867.

Stegle, O., S. A. Teichmann, and J. C. Marioni. 2015. “Computational and Analytical Challenges in Single-Cell Transcriptomics.” Nat. Rev. Genet. 16 (3): 133–45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25628217.

Some care is taken to account for missing and duplicate gene symbols; missing symbols are replaced with the Ensembl identifier and duplicated symbols are concatenated with the (unique) Ensembl identifiers.↩︎

The number of expressed features refers to the number of genes which have non-zero counts (i.e. they have been identified in the cell at least once)↩︎

This is consistent with the use of UMI counts rather than read counts, as each transcript molecule can only produce one UMI count but can yield many reads after fragmentation.↩︎

It is important to note that we only using droplets assigned to a sample (i.e. we ignore

Unknownsamples) for the calculation of these thresholds.↩︎This is a large number of HVGs but the results don’t qualitatively change by reducing this to, say, the top-1000 HVGs.↩︎

Note that the converse is not true, i.e., there is no guarantee that the retained PCs capture all of the signal, which is only generally possible if no dimensionality reduction is performed at all.↩︎